History of Rangers

The Park Ranger: From the Wild West to Colorado's Suburban Frontier

Few characteristics of the American experience are as central to the self-image of the people of the United States as the nation's frontier heritage. The formation of American virtues by contact with a wild, unsettled edge of civilization appears over and over in the arguments that led to the creation of national, state, county, and regional parks and wilderness areas. And so it is no surprise that the people who take care of these places-America's county, state, and national park rangers—would embody some of the characteristics Americans have long associated with the frontier.

The idea that a line of demarcation between the civilized and the wild formed the essential self-reliant and democratic character of the American people was most famously advanced by Frederick Jackson Turner in a paper delivered to a Chicago meeting of professional historians in 1893. In his paper Turner delivered the news that the frontier was closed, having swept across the country all the way to the Pacific. At the same time Turner advanced the idea that the frontier experience formed the American character. It is worth noting that Turner's notion of who the Americans were was less inclusive than that of today's historians and this selectiveness promoted a more positive version of the frontier than the stories of those whose land was confiscated to make homes for Turner's Americans—Native Americans and Mexicans.

Turner was not the first to see the passing of the frontier. At least thirty years before him, some Americans saw the frontier as threatened by its own chief characteristic, the rapid subordination of natural wonders and open spaces to economic production. If someone had been around to take a time-lapse movie of it, the frontier would have been revealed to be a sweeping wave of barbed wire fences, cattle, railroad tracks, clearcuts, piles of mining waste, new towns and rapidly-growing cities (some of them quite prosperous and beautiful), and a hail of gunfire mowing down wild animals. The rate of change was not impossible to see, even at that time, and this resulted in a unique situation where a sense of nostalgia for a lost frontier came before the loss of it. For example, the 1872 creation of Yellowstone National Park to protect the threatened wonders of the Yellowstone Plateau predated by four years the 1886 slaughter of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh Cavalry by the Cheyenne and Sioux at Little Big Horn.

Today, American park rangers trace their lineage to a man named Galen Clark. In June of 1864, in the middle of some of the bloodiest months of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill to transfer the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa groves of giant Sequoia trees from the federal government's General Land Office to the State of California in order to preserve these wonders for the public in perpetuity. The care of the new state park was given by the state to a commission that included the great landscape architect and designer of New York's Central Park, Frederick Law Olmstead.

It soon became clear to Olmstead and his fellow commissioners that protective laws without law enforcement were useless. And in 1866, they appointed Clark, an immigrant from the East who had become a capable mountain man and outdoorsman, as "Guardian of Yosemite." Clark's essential duties are recognizable as those of the modern park ranger: He helped people find their way around the park, taught them what he knew about its natural wonders, and when necessary employed the authority given him by the California Legislature to stop visitors and residents from damaging the place.

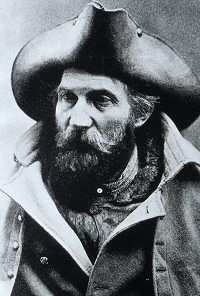

The first real national park—portions of Yosemite would remain under the control of the State of California until 1906-was created by an act of Congress in 1872 to protect over a million acres of bubbling geothermal springs, herds of wild animals, and scenic vistas of Yellowstone. As had been true in Yosemite the federal government soon found that laws without law enforcement didn't work. From 1873 on, a series of local men were given authority to prevent damage and mayhem there. Most well-known of these was a mountain man and former Civil War soldier, Harry Yount, who was appointed in 1880. It was Yount, as quoted by Butch Farabee in his history of the American park ranger, who identified the essential failure of these first appointments in his letter of resignation the following year:

"I do not think any one man appointed by the honorable Secretary...is what is needed...but a small and reliable police force of men....is really the most practical way of seeing that the game is protected from wanton slaughter, the forests from careless use of fire, and the enforcement of all other laws, rules, and regulations for the protection and improvement of the park."

Yount, Clark, and their fellow guardians would struggle not only with lawless acts that threatened the park and its animals themselves, but with unruly behavior that threatened the peace and safety of visitors. In 1879 the superintendent of Yellowstone sent an employee of the park, N.D. Johnson, to arrest one James McCawley for drunk and disorderly behavior. McCawley had been involved in a fistfight and attempted to ambush and attack the men he had fought with the next day. Johnson is reputed to have survived the assignment. Three years later Clark's successor at Yosemite would report:

"Sometimes we are visited by rough characters from the mountains who, when crazy with liquor, not only become nuisances, but sometimes endanger human life."

Then and now, the strain between the duty to regulate human behavior and more nature-oriented duties-teaching people the names of the flowers, collecting scientific data, preventing alien plants and animals from infesting the parks, and so on—have been widely perceived by the public, by the rangers, and by park management as a problem in itself. But it is a problem for which park rangers are on the whole well-prepared. Modern park rangers hold educational and professional qualifications in a wide variety of fields, including firefighting, history, archeology, wildlife management, teaching, and emergency medicine. The sheer variety of the job calls for a particularly versatile kind of person in a time when the rest of the American workforce is increasingly specialized. Many rangers are proud of this versatility and point to it as the principal difference between them and workers in almost any other field.

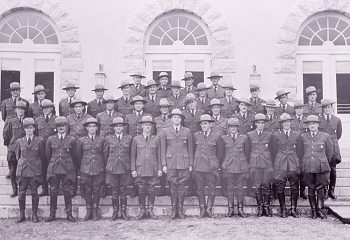

In the 1970s, major postwar improvements to highway travel and the rapid expansion of suburbs into open lands created a sense of emergency among conservationists. By 1977 an estimated five million acres a year of farm and ranchlands were being lost to suburban sprawl. And in areas where governments had failed to secure greenbelts, the citizens of older suburbs were cut off, tens of miles from the nearest patch of green where they could stretch their legs or let their children run around and play. As the threats to quality of life became clear, county and regional governments began to acquire millions of acres of regional open space lands to protect important recreational opportunities such as boating, hiking, picnicking, and mountain biking close to the places people lived. As had occurred a hundred years before, the protection of these lands under new laws was only a prelude to a search for people to enforce those laws and provide other necessary services. As was true at the state and federal level, the legal and professional demands upon this growing workforce of county and open space rangers led to increasing professionalization. As a result, these smaller, newer agencies are among the most innovative and dynamic in the nation and they now compete with national and state governments for the best and brightest young rangers. As these rangers mature in their careers, they are retained by their agencies due to better access to schools and shopping facilities than some of the more remote postings in state and national parks.

Today, the frontier in land management can be said to be on the edge of burgeoning suburbs where people by the thousands meet wild nature. And while today's conception of the frontier is more inclusive and problematic, the men and women rangers who take care of Colorado's regional and local parks come from all backgrounds and are, like frontier men and women, resourceful, thoughtful, independent, and capable. Most of all, they are enthusiastic about the wide open spaces they protect and proud of the level of service they provide.

© 2009 by Jordan Fisher Smith, all rights reserved

Click a photo to enlarge.